These are strange times to be alive.

A rapid evolution is afoot, and man himself is the one driving it—although, if all goes according to plan, he won’t be driving much longer.

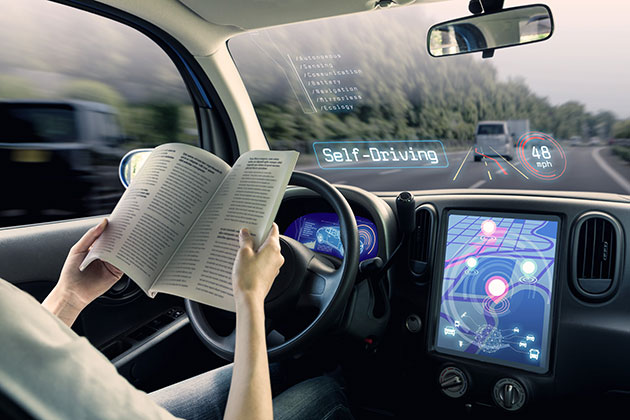

Autonomous cars are developing rapidly, more capable of handling our roads every day.

In anticipation of the impending takeover, automakers have steadily introduced us to the idea of self-driving cars, adding new features with each model year that bring our vehicles one step closer to taking total control—and further remove us from the responsibilities of driving.

The slow-drip approach not only allows for more time to test and tweak new programs, it lets us ease into our new role of consummate passenger—and broker a trust with our mechanical chauffeurs.

But it may have worked too well.

The act of “physically manipulating handheld devices” behind the wheel is on the rise, especially among younger drivers, the latest statistics from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) show. And last year, highway deaths reached higher levels, totaling 40,200—marking a 6% jump from 2015 and the first time the number has breached 40,000 in nearly a decade, according to the National Safety Council.

One of the biggest arguments for self-driving models is their ability to make our roads safer. Indeed, some researchers have predicted the cars could cut roadway accidents by up to 90%. But in this strange interval of history, before the computers have mastered all our street smarts, we must still retain some skills, even as we’re encouraged to forget them by advancing technology.

It’s proved a difficult—and deadly—tightrope walk. And some experts fear that, before it gets better, it will only get worse.

Vestigial Skills

People are not only driving more distractedly, they’re driving less actively, even when they’re paying attention.

It’s called atrophy. In the medical profession, it refers to an organ or muscle that withers with underuse; but when it comes to our driving skills, the decline in sharpness has come from increased neglect.

A new study from the University of Michigan offers a glimpse of this evolutionary trick in motion.

The research looked at 108 drivers and the ways they interacted with new blind-spot detection systems over the course of 6 weeks. The program, installed in a fleet of Honda Accords, alerts drivers to cars present in the notoriously out-of-sight areas with chimes and warning lights. And dependency upon the system set in rapidly.

Over the course of the study, the researchers found a marked increase in drivers who stopped looking over their shoulders at all while changing lanes. The participants, instead, began relying entirely on the warning system. (All told, nearly three-quarters of the drivers said they’d want the same technology in their personal vehicle.)

“The more they are exposed to these systems, the more they trust the systems,” Shan Bao, associate research scientist at Michigan’s Transportation Research Institute, told Bloomberg News. In emergency situations, “they’ll trust the systems more than they’ll trust themselves.”

And it’s not just blind-spot watching that is available in new models. Current driver-assist features can do everything from slam on the brakes to parallel park.

As semi-automated options have increased, so has the awareness of a potential dependency on them, with 57% of drivers themselves predicting the erosion of their own skills with the introduction of driver-assist technology, a recent Kelley Blue Book survey found.

Give & Take

But even a self-aware reliance can turn out to be deadly.

The driver killed during a test run of Tesla’s autopilot system in 2016 reportedly had his hands on the wheel for just 25 seconds in the last 37 minutes before the car crashed.

While automakers have continued pushing their vehicles up the autonomy scale, they have also started addressing the problem of inattention, scrambling to find stop-gaps to keep us focused for as long as we’re still needed behind the wheel.

And to fully look over our driving experience, our vehicles will not only need to borrow our knowledge but some of our senses.

The new programs being installed in vehicles to keep us on the straight-and-narrow can literally keep an eye on us. General Motors has introduced technology that tracks a driver’s gaze while on the road, ensuring he or she isn’t looking away for too long. Toyota and Audi have developed similar features for some new models.

Meanwhile, Nissan and Tesla, among others, have focused on the sense of touch. Built-in systems on some of the cars record the pressure of hands on a steering wheel, and will begin issuing warnings after several seconds where it doesn’t feel any. In some models, the car will eventually begin pumping the brakes, and even stop the car if no hands are returned to the wheel.

Still, in its attempt to help, the programs may continue to hinder us, transferring our dependence from the actual automation of the car to the reminder systems.

The Waiting Game

As cars have continued adapting, we’ve classified their skills into 5 levels of autonomy, with the fifth representing the ultimate driverless vehicle.

With most currently available models at level 2, and many with the capability of reaching level 3, we’re sitting in the exact middle of the chain; the very epicenter of the tectonic rearrangement of our transportation.

As we continue the climb toward advancement, we may reach the peak just in time to watch the twilight of our own usefulness behind the wheel, and the new dawn of the machines.