My first boyfriend was a motorhead. I was 16, too young yet to drive in New Jersey. He was a high school senior and had an awesome car.

He tinkered on it constantly, and I must admit, I loved cruising around with him and feeling what each new engine tweak or wheel alignment would allow the thing to do. The faster his car got, the more I seemed to like him.

True to young love, the relationship was fickle, and fizzled out after just a few months. I wonder now if he had picked me up for that first date in a slow self-driving vehicle, whether I would’ve been interested at all, and saved myself the heartache.

Of course, my young beau couldn’t afford anything top of the line, but that type of problem—the boring consistency of an automated chauffer—is exactly what many luxury car makers are now worried about.

As the rigid grip of algorithms slowly wrest the steering wheels out of our hands, those manufacturers have begun to openly wonder: Will anybody drive for the thrill of it anymore?

But in an era that has seen the death toll of driving accidents steadily climb, a better question to ask may be: Is the thrill worth it?

The Drive to Drive Fast

If going fast is so potentially perilous—and it is—why do we like it at all? The sports car industry surely wouldn’t exist if there weren’t enough enthusiasts in the world who, while appreciating the beauty of the machines, were really out to satiate their thirst for excitement.

It seems that survival of the fittest wouldn’t allow for the passing down of such a risky tendency, but the need for speed—or at least, the pleasure derived from doing something dangerous—is a direct result of our evolution.

Scientists call the behavior “novelty seeking,” and it’s what made early homo sapiens willing to travel across an uncharted world. The inclination to do daring deeds was also closely tied to human survival. It’s what encouraged us to take risks while hunting, ensuring that those brave enough to face the perils of the wild would come back with a fresh supply of meat for the tribe.

With the advent of grocery stores and moving companies, we’ve long since needed this personality trait to stay alive, but the biological preference tying risk to reward—through the brain’s simultaneous release of adrenaline and serotonin, the hormone responsible for making us happy—has endured. That’s what makes driving fast feel like such a rush.

It’s ensured the longevity not just of the human race, but of the luxury car market. At least, so far.

Evolving Past Adrenaline?

Of course, the danger of sports cars is only one aspect of their charisma. Very few driving enthusiasts can resist the visceral pleasure of a powerful, purring engine. And the knowledge that your machine can outperform all others on the road is priceless to some.

The tangible price of the vehicles—marking their abject exclusivity—is also a huge factor of their desirability. And their sleek, aesthetically-pleasing designs don’t exactly hurt their appeal.

But those priorities seem increasingly antiquated in a world more focused on sharing its rides than showing them off, and with the simultaneous rise of self-driving vehicles, luxury car brands are worried that future generations won’t even have a gas pedal to punch, let alone the skills to cruise around curves. (In fact, the CEO of BMW recently admitted that 80 percent of BMW owners showed a serious lack of knowledge in their cars’ basic mechanics.)

Executing speedy, sharp turns or navigating your car across snowy slopes may look cool in a commercial, but a steadily increasing number of Americans aren’t even legally sanctioned to try those skills out. (Sixteen-year-olds alone were 47 percent less likely to have a license in 2014 than in 1983, according to a recent study.)

In the face of such a sea change, many primo auto makers have turned inward—literally.

Upcoming models for brands like Volvo and Mercedes have focused more on improving what drivers can do with their cars—Surf the web! Tweet via voice command!—than what the cars can do for their drivers.

Further changes to the industry imagined by Google—and recently helped along by a government designation declaring autonomous technology legally equivalent to a “licensed driver”—would mean that self-driving cars of the future wouldn’t even need a steering wheel or pedals to be street legal.

This frees up car makers to double-down on their interior focus, creating larger, more comfortable seating, and bringing vehicles one step closer to becoming not a tool of transportation or even a vessel of excitement, but a place where people “watch a movie or whatever,” as Volvo CEO Hakan Samuelsson explained to Bloomberg news.

Exploiting the Trend

Ride sharing and autonomous vehicles have changed the game, and along with it, the definition of luxury.

Once describing the extravagance of owning the best car on the road, “luxury,” in our technological age, has become more about the freedom from the responsibility of driving at all.

Driving has become a chore; a task we outsource to strangers through our phones, so we can spend more time on our devices while in the backseat of our rideshares. Once autonomous cars hit the scene, even those rideshare drivers won’t have to worry about getting behind the wheel.

But what’s bad for the goose in this case is great for the gander.

Society is already primed for sharing rides. And motorheads everywhere—or just business-savvy individuals—can capitalize on this tendency, offering to rent their own flashy vehicles out for a short period of time.

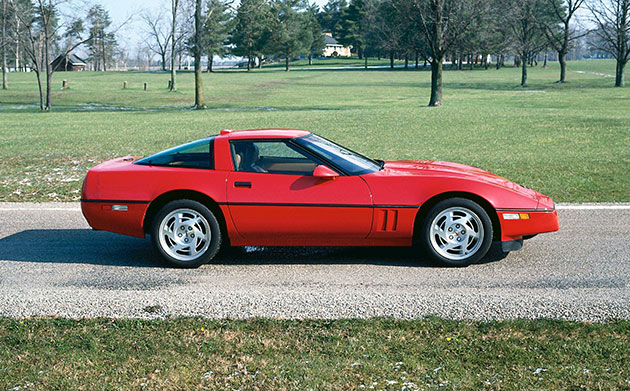

The luxury price tag of a Corvette or Ferrari look a lot nicer when they could be paid off—at least partially—with the help of such income. And in an imagined future world where few have driving skills at all, this could give holdouts the chance to chauffer others around and collect even more cash for their efforts.

Scarcity has always been a factor in creating demand. It’s a basic principal of economics. But at a time when these cars would be scarcer than ever, the dream of owning one would become even more attainable for the true believers.

Reassessing the Risk

While the supply of these designer vehicles could be shaky in the future, such a downward trend would beg the question: Do we need them at all?

Our personal communication devices have already proved so disruptive that they’re now involved in a soaring number of driving fatalities each year. Building an ultimate driving machine, then, would require you to have the ultimate trust in your customer to not drive distractedly—a much bigger ask now than it has ever been in the past.

Those numbers also contrast sharply with incoming data on self-driving vehicles. Between removing dangerous drivers from the road and standardizing driving practices, automated cars have the potential to help save up to 32,000 lives annually in America alone, according to numbers cited earlier this year by Christopher Hart, chairman of the National Transportation Safety Board. (The issue of exactly whose lives the cars would be programmed to save, however, is still up for debate.)

While it’s still unknown how government regulation of self-driving vehicles would affect how powerful the cars could be made, how fast they could go or how much torque they could have, those points seem moot when the thrill of being in personal control of those factors would be gone. On balance, the excitement of driving may be one risk that’s not worth the reward.

Still, we shouldn’t be too eager to sell out our humanity.

While our cars morph into mobile movie theaters or private party pods, the world will pass us by, unnoticed from our new vehicles’ windows (if they’ll have windows at all). What then, becomes of the chance to see what’s around you? To learn through observation the nuance of your neighborhood or the endless variety of landscapes?

Driving fast may trigger the reward felt by our ancestors for taking risks, but the drive itself—and what it exposes us to—hits that second advantage of novelty seeking: the one that rewarded us for seeing new places and learning new things.

Regardless, society will change, but no matter how different it becomes over time, some things will likely remain the same. High school students will still strive to impress their dates. In the future, they’ll just have to figure out how to do it without a cool car to show up in.