Our Digital Age has been one of disruption, with new computerized capabilities wielded like flaming swords to cut down old competitors, raze outdated industries, and blaze new trails forward.

But the tech world’s latest pet project will really hit us where we live.

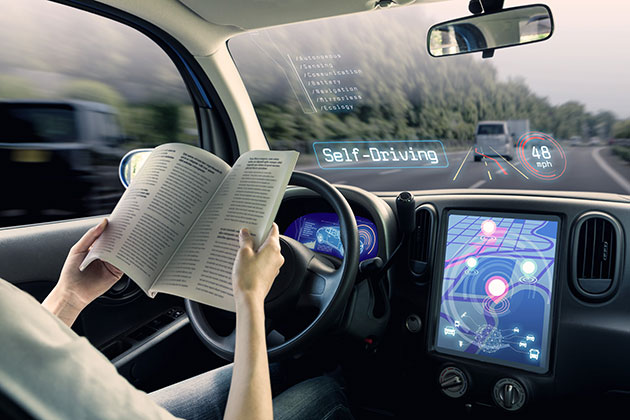

Self-driving cars have the potential to change nearly everything about our world, from how we get around to where we settle down.

The burgeoning technology will change the face of personal transportation, long in a symbiotic relationship with our personal dwellings, opening up not just the shapes of our roads but the designs of our neighborhoods to completely new interpretations.

As the development of driverless vehicles moves ahead at full speed, we may want to hit a rest stop and think: What will those changes look like, and how will they impact us?

While hard data is virtually nonexistent—as the vehicles are still at least several years away from taking over our roads—a group of top thinkers in conservancy, land use, and urban planning weighed in on the idea, using a mix of imagination and expertise to guess what the landscape might look like once the dust has settled.

And it’s not all pretty.

Living on the Edge

The future is, as they say, not ours to see, and not even the most well-educated experts could truly predict the full impact of changing something so integral to society.

But as the progress of self-driving cars continues to creep, many have begun to worry about how our communities may crawl.

The spread of suburban development could explode under autonomous vehicles, with the cars creating a worry-free ride to work—and with it, less incentive to live by the office.

“When you increase supply of highways, you can induce new development and new sprawl,” said Rob McDonald, lead scientist for the Global Cities program at The Nature Conservancy, a nonprofit focused on conservation issues around the world. “To me, it’s quite a likely chance, if you make commuting more convenient and less of a negative experience, people will accept longer commutes for cheaper living.”

Such further-out neighborhoods will be less costly than city centers—the rub being that, even with telecommuting capabilities, many employees will, most likely, still be tied to a physical office location and expected to show up at least once in a while, McDonald explained.

“In the ‘90s, a lot of papers were saying that the Internet will destroy cities,” he said. “That hasn’t happened. What are cities for? Even in the Internet era, there’s a lot of value in face-to-face contact.”

While there’s no current studies examining the potential impact autonomous vehicles could have on commute time, history has plenty of stories to tell—and lessons to offer. The self-driving car is just the latest in a long line of newer and faster transportation supplanting an aging, present-day model, McDonald said.

“There’s an interesting argument in urban planning,” he said. “Over centuries, since people were walking and using horses, people have tried to keep their commute under an hour each way. When you have a new technology like trollies or commuter rail or highways, the average speed increases, so metro areas spread out a little bit.”

The idea, he said—and explained in a detailed blog post last year—is that the efficient nature of self-driving cars would make that hour zip by, tempting the masses to push further away, since they could use the newfound time to sleep, relax, or even work on their way to work.

He cited the experience of a friend as an example. While her job allows her to work remotely, and make the hour-long commute to Baltimore just once a week, she told him that the opportunity to take that ride in an autonomous vehicle would persuade her to visit the office every day, McDonald said.

The issue is also a concern of Christa Cassidy, an infrastructure and land use program manager at the Conservancy’s California branch.

“You could feasibly live in Tahoe and work in San Francisco and sleep on your commute or work on your commute,” she said. “It’s a pretty extreme example, but with housing prices being the way they are in California, there aren’t the right policy mechanisms in place.”

Specifically, she mentioned the skyrocketing costs of living in California’s cities, and the large disparity between rent in those places and less-developed areas of the state. A connection allowing easy access from one to the other could prove popular, increasing sprawl in those outlying communities.

And while no policies yet exist to keep the creep of suburban sprawl at bay in an age of self-driving cars, regulators are starting to consider their options, she said. In California, that includes the idea of road charging, in which a fee is prescribed to the number of miles traversed in a given year, made payable at the DMV.

Still, Cassidy said, that system is problematic in other ways, essentially acting as a road tax that would disproportionately affect those living farther away—and likely making less money.

“Only the uber-rich can afford to live in these city centers, and those with less means are living further out—and would also be taxed more,” she said. “It’s similar to the gas tax now: Those who are wealthier have the electric vehicles, so they’re not paying into the tax structure that supports our infrastructure and road systems—and poorer people, with the big junkers that are getting 8 miles to the gallon, are paying a disproportionate amount.”

But for all the threats they pose to open spaces on the outskirts, self-driving cars could create opportunities for urban centers that need more of it.

Seeing Green

One possible benefit of autonomous vehicles that is widely agreed upon is their ability to eliminate the need for parking.

The robocars could theoretically exist in a cycle of dropping one set of passengers off, then picking up another, reducing any need for stalling or stopping and releasing untold acres of space—and nearly 1 billion parking spots—reserved for housing idle vehicles nationally.

The effect would likely be felt most keenly in urban centers, which dedicate a larger portion of their already overtaxed land to parking. In New York City alone, nearly 24 miles of potentially freeable space has been identified.

And with the opportunity to rethink land use on such a large scale, it’s important for cities to keep the bigger picture in mind, McDonald said.

“There’s going to be close to 3 billion more people in cities by 2050,” he said. “We’re going to urbanize an area the size of Texas, if you push it all together—so it’s getting the shape of those cities right, so you’re protecting critical natural habitat for species and providing parks and trees so those cities are livable.”

The areas could also be used for infill, to build more housing or areas for urban agriculture, many have proposed.

Still, this vision is heavily dependent upon whether the idea of owning a personal vehicle can survive the self-driving revolution, said James Anderson, director of the Justice Policy Program at the RAND Institute for Civil Justice.

“If you move to more of a shared-vehicle model where you’re summoning your Lyft or your Uber from your cellphone and transportation is really viewed as a service, we could move away from the single vehicle ownership model—then you could see less need for parking,” he said. “The rosy story is you can replace parking lots with parks and replace on-street parking with bike lanes, and try to move to a more pedestrian- and bicycle-focused vision of the street.”

As of now, it seems we’re headed toward that rideshare-friendly future. By 2030, a quarter of all miles driven in the United States could be in publicly-shared, electric, self-driving cars, according to a study by the Boston Consulting Group.

Cassidy also forecasted the trend.

“People up through their 40s will be the last generation to associate individual car ownership with sexiness and freedom and independence,” she said. “Lyft and Uber are driving this because it reduces 80% of their overhead. Ridesharing companies will be developing the self-driving technology, so there will be less need for parking in cities.”

With so much space open for reinterpretation, we could truly change the landscape, but to achieve that goal we must do more than think locally—we must act globally.

Dreaming Bigger

Managing such substantive change in one city is no easy task. Tracking it across large swaths of land is patchwork at best—and much more typically problematic.

“We’re probably going to be planning over a larger area, so one of the challenges, especially in the U.S., is a lot of our political decisions are at the scale of a municipality,” McDonald said. “A smart way to do that plan is to think about the whole metro area, but there are dozens of municipalities with their own governments, their own powers, their own plans.”

How to get them all in accordance, he said, would be the question. But California may have already found a possible answer.

In 2008, state lawmakers passed legislation creating 18 metropolitan planning organizations across the state, each responsible for drafting its own regional transportation plan and sustainable community strategy every 4 years. The goal of each district is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by state-mandated levels, in part by lowering vehicle miles traveled in their areas and developing more infill projects.

The latest proposals were submitted in January of last year, written during a 4-year span that saw the rapid growth of autonomous vehicle development. And while the newest reports make little mention of the possible effects the new-age transportation could have on such policies, the next round—due by 2020, a year before many automakers are promising the release of their first self-driving models—very well could, Cassidy said.

“We’ve been taking a pretty hard look at high-speed rail, and it’s not necessarily happening as fast as a lot of people thought it was going to at some point,” she said. “Now, we’re thinking that autonomous vehicles could be what to focus on. It’s all market-driven, so it’s moving faster. Now, it’s ‘Is this something we should be looking at?’”

Still, all three of the field leaders said that, for now, most of the discussion around the topic similarly ends in question marks.

“At this point, it’s mostly conjecture,” said Anderson, at the RAND Institute. “It’s almost surely the case that we’re going to miss certain things and be hopelessly wrong, and embarrassingly so.”

“You always try to hang on to that idea, have some humility about it, and recognition that it’s really hard to predict the future, and particularly now, when there’s so much uncertainty.”